Untying the Valknut

Symbolism, Etymology, and Interpretation

The Valknut is one of the most common ancient Norse symbols and it remains one of the most intriguing, cryptic and controversial motifs from the Viking Age. Comprising three interlocking triangles, either as a unicursal symbol consisting of one single continuous path such as on runestone G 268 or as a tricursal form consisting of three separate triangles such as on the “Stora Hammars Stone”, this obscure icon is immersed in mystery and debate.

Little is known about the symbol – right down to the actual name for it, where “Valknut” is a modern invention. However, it has been subject to various interpretations, each adding depth and interpretation to our understanding of its significance.

In the following we hope to clarify at least some of the confusion around the symbol.

Symbolism and Interpretation

The word “Valknut” is often assumed to be a compound term that combines “Valr”, meaning a warrior fallen or slain in battle, and “knut”, meaning knot. As such the terms translates to “knot of fallen warriors.” The term “valknute” in Norwegian has been attributed to a 1943 paper by Gutorm Gjessing (available here) when referring to the symbol on for example Stora Hammars Stone as mentioned above. However in modern Norwegian the term “valknute” usually refers to the symbol known in English as “Saint John’s Cross”, most commonly recognized from the symbol on the Mac-keyboard.

The exact symbolism behind the Valknut is as mentioned not known, however several interpretations exist. One popular perception is that it represents a connection of three realms of Norse cosmology: Asgard (the world of the gods), Midgard (the world of humans), and Hel (the underworld) – or equally birth, life and death. This tripartite structure partially mirrors the Norse understanding of the universe, reflecting the interconnected nature of all things, for example as embodied by the three “norns” who weave the web of fate.

Relating the symbol directly to Odin and his role in this interplay, for example Hilda Ellis Davidson suggests it might be associated with his power to bind and unbind. According to legend, Odin could bind the minds of men, forcing them into behaving as he wanted. Our brand name jarðfé is even taken from a passage attesting to Odin’s ability to do just that:

Óðinn vissi um alt jarðfé, hvar fólgit var, ok hann kunni þau ljóð, er upp laukst fyrir honum jörðin, ok björg ok steinar, ok haugarnir, ok batt hann með orðum einum þá er fyrir bjoggu, ok gékk inn ok tók þar slíkt er hann vildi.

Odin knew about all buried treasures and where they were hidden, and he knew the songs which would open up the earth, mountains, stones and hills, and just with his words he bound those who lived there so he could take what he wanted.

The interlocking triangles could therefore represent the entwining of the mental and physical, highlighting Odins control over life and death.

Another interpretation relates to the combination of three triangles, resulting in a symbol consisting of nine corners, a number considered magic in old Norse and Viking symbolism. Odin hangs himself on Yggdrasil for nine nights, there are nine worlds surrounding Yggdrasil, the length of symbolic feasts lasted nine days and is supposed to have included sacrifice of animals and humans in groups of nine, etc. The list of times the number nine comes up in old Norse mythology is very long, and speaks to its ingrained symbolism.

Rudolf Simek in his “Lexikon der germanischen Mythologie” and others have also suggested the Valknut’s association with the symbol known as “Hrungnishjarta”:

Hrungnir átti hjarta þat, er frægt er, af hörðum steini ok tindótt með þrimr hornum, svá sem síðan er gert ristubragð þar, er Hrungnishjarta heitir.

Hrungnir had a heart, that was famous, it was made of stone and pointed with three horns, like the symbol that was later drawn, known as Hrungnishjarta.

Note that “hornum” could either be translated as “horn” (ref horn in Norwegian), as in the bone-like growth on some animal’s heads, or “corner” (ref hjørne in Norwegian), as in the corner of a square.

This interpretation is in our opinion less likely, as the stanza specifically notes that the symbol has three pointed horns. Both versions of the valknut will have six or nine horns or corners depending on how one counts, making it more likely that Hrungnishjarta refers to a symbol such as the one found for example on the runestone G 268 or that on runestone G 181, both from Gotland in Sweden.

Valknut and its connection to Odin

The Valknut is frequently found in archaeological contexts connected to Odin and it is therefore sometimes known as “Odin’s knot”. It has also been found on gravestones and urns, earning it the epithet “death knot” as well. The common theme of the symbol’s usage in art has in most circumstances been in relation to war or death, possibly suggesting its use as a symbol of mortality and the transition between life and death. This interpretation also supports the link to the god Odin and his association with war, death, and the afterlife.

Now, there has been a lot of modern debate about accuracy of exactly this. Some popular online references go very far in making the claim that the valknut has no symbolic value, that it is simply a Norse re-imagination of a triquetra and the suggestion has also been made that because it is often associated with horses the symbol is simply related to horse worship.

However, reading the article by Gutorm Gjessen, who is often attributed as the father of term he states:

[… på] St. Hammars [steinen] var det plasert tre triangler, flettet i hverandre, stort og tydelig og demonstrativt like under ørnen, som en må tro er Oden. Det er ikke tvil om at trianglene står her som et rent symbolsk tegn, og det ville være fristende å oppfatte det som et Oden-symbol, plasert her for å vise den, som måtte være i tvil, at ørnen er Oden sjøl. Det må da ha vært et symbolsk tegn, som var velkjent for alle, som skulle se bildesteinene.

or in English (our translation):[…] on the “Store Hammars Stone” there were three interwoven triangles prominently displayed right below the eagle, which one would interpret as being Odin. There is no doubt that the triangles are a purely symbolic sign, and it is tempting to interpret the symbol as a symbol for Odin directly, placed exactly here to convince those in doubt that the eagle was in fact Odin himself. It must therefore have been a symbolic sign, known colloquially to everyone who would see the stones.

This is from the first mention of the term “valknute”, and he goes on to mention another five runestones where the symbol shows up related to horses and he also mentions a few stones in which the symbol is seen together with ships. The interpretation is most often that these ships depict a journey into the afterlife. Interestingly though, a well-known kenning for ship was horse, such as “bárufákr” meaning “wave-horse”.

The point made by Gutorm Gjessen is nonetheless clearly that he believed the symbol was a direct symbol for Odin himself. But Gjessen also goes much further in his discussion, also including symbols such as the one found on GP 184 Hejnum Riddare or Alskog Tjängvide I. This makes it is that Gjessen’s interpretation of the symbol is much wider than the modern interpretation of the valknut as just a triangular symbol.

Interestingly, Gjessen refers the choice of the term “valknute” partially to Einar Lexow’s book “Gammel vestlandsk vævkunst”, which really deals with the Saint John’s Cross mentioned above and it’s use in Norwegian traditional weaving. He also states that the symbol is known by this name in western Norway and Swedish

Selv om valknuten ikke er kjent fra gammelnorsk litteratur, er det tydelig nok at den er gammel i målførene også som navn på det bestemte ornamentmotiv. Endelig kan den magiske kraft ornamentet har hatt i senere tider, tyde på at denne kraft er en reminisens fra en religiøst-symbolsk mening, som det en gang har hatt.

Even though the valknut is not known from old Norse literature, it is evident that it has along history in common language, also as the name of the specific ornamental motif. Finally, the magical power the ornament has had in later times may reflect that this power is a remnant of a religious-symbolic meaning, which it once had.

According to Gjessen, “valknute” was the Norwegian name of the symbol. Note that we will discuss this further below.

Rudolf Simek, even if he interprets the symbol as the same as Hrungnishjarta, also has the same interpretation as Gjessen, even going further and suggesting its direct relation to death

Der norwegische Name dieses Zeichens und die Tatsache, daß es auf Bildsteinen durchwegs mit Odin gemeinsam auftritt und noch dazu auf Grabbeigaben des Osebergschiffes eingeschnitzt ist, weisen ihm eine Rolle im Totenkult zu.

The Norwegian name of this symbol and the fact that it consistently appears together with Odin on picture stones and is also carved on grave goods from the Oseberg ship assign it a role in the cult of the dead.

Simek obviously bases part of his conclusion on the idea that the Norwegian name for the symbol was “valknute”.

The main source of the disagreement in academic circles seems to stem from conclusions made by Tom Heller and his book “Valknútr: Das Dreiecksymbol der Wikingerzeit” which is arguably the most significant examination of the symbol known to date. Unfortunately, we have not been able to get a copy of this book and cannot make any statements to its conclusions, however Leszek Gardeła in the paper “Miniatures with Nine Studs” makes the following comment:

The occurrences of the valknútr motif in Viking Age iconography have been thoroughly investigated by Tom Hellers (2012) whose work convincingly demonstrates its ties with Óðinn as well as with the ideas of death, afterlife, and magic.

and then goes on to note

In approaching the valknútr, Hellers advises caution and rightly refrains from providing one overarching explanation of this evidently potent symbol. Instead, he advocates the idea of its multivalence and underlines the fact that it operated within an exclusively pagan context.

Evidently to Gardeła, the conclusions by Tom Heller are mostly the same as for the other above mentioned researchers, although he emphasizes Hellers’ view that the symbol must be seen in context.

Etymology

Fundamentally it seems much of the debate online about the “validity” of the symbol valknut seems to boil down to a discussion about whether or not the real name for the symbol in question was “valknut” or “valknutr”. And equally the etymology of this word. Much of this again seems to boil down to Gutorm Gjessen’s article, where he notes:

I yngre merovingertid var valknuten altså et Oden-symbol. Det ligger da unektelig nær å utlede forstavinga val- av valr m. = de falne (i strid). Oden var fram for alt de falnes gud, og valr har gitt opphavet til Oden-navnet Valfader, til Valhall og valkyrje, og til en mengde andre sammensetninger.

In younger Merovingian times, the valknot was threfore a symbol of Odin. It is undeniably reasonable to derive the prefix val- from valr, meaning “the fallen” (in battle). Odin was above all the God of the fallen, and valr has given rise to the name Valfader referring to Odin, to Valhalla and valkyrie, and a number of other compounds.

On the basis that the term for the symbol (or this and a range of similar symbols) is “valknute” in Norwegian and the symbol has been juxtaposed with depictions of Odin in old Norse time, he makes the reasonable connection between the prefix “val-” in “valknute” and the similar prefix “val-” in old Norse which we know beyond a doubt refers to “valr” or “the fallen”. He then goes on to note

En annen ting er, at det kanhende kan virke unaturlig å stille valr sammen med knute, hvorfor Magnus Olsen tidligere har antydet overfor Einar Lexow, at ordet kunne henge sammen med folkenavnet valir = kelter, særlig fra Valland.

Another point is that it might seem unnatural to combine valr with knot, whereuopn Magnus Olsen previously hinted to Einar Lexow that the word could be connected to the word valir, meaning Celts, especially from Valland.

This is taken from Einar Lexow who relates that the well-known Norwegian philologist and expert in old Norse Magnus Olsen suggested the name could also have been a Norwegianization for the term “Celtic knot”. Note that “Valland” was the old Norse word for western Europe (read more here).

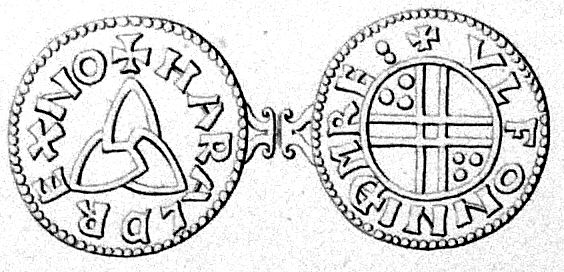

Einar Lexow also notes that “valknute” was used by G. I. Schive in “Norges Mynter i Middelalderen” (1865) to denote the symbol found on the coin minted by Harald Hardrada, more commonly known in English as a triquetra

We should note that this symbol seems more closely related to our rendition of the symbol, than the symbol in current Norwegian use. The difference between this symbol and the valknut seems to be a rounding of the sides of the triangle and that the triangles hinge in their corners. However, Einar Lexow notes that he believes Schive’s use of the term for the symbol in question is in error and due to a misunderstanding.

The truth is that there exists a series of books written in the 1800s, mainly about coins, that call this exact symbol a valknut. For example “Aarbøger for nordisk oldkyndighed og historie” from 1875 describes the same symbol as Schive as a “valknude” on page 135:

De tyske numismatikere kalde i almindelighed deres figur en gordisk knude; de nordiske møntkendere bruge den heldigere betegnelse: valknude […]

German numismatists generally call their figure a Gordian knot; the Nordic coin experts use the more fortunate term: valknude […]

Note that “valknude” is the “Dano-Norwegian” equivalent of the “valnute”. The interested reader may refer to Wikipedia.

While “Urda, et norsk antiqvarisk-historisk tidsskrift” from 1837 (page 395) calls the following symbol(s) a valknude:

Anders L. Lorange in “Samlingen af Norske oldsager i Bergens museum” from 1875 calls the same symbol also a valknute, when discussing the same item as above.

“Nordisk universitets-tidskrift” from 1857, on the other hand calls the main knot-structure on the Fjuckby runestone a “valknut”.

And in “Supplement” to “Lexicon over adelige familier i Danmark, Norge og Hertugdomene” from 1872 Chr. C. L. v. Castenskiold calls two intertwined ropes a valknude.

It therefore becomes evident that the tradition in Scandinavia was to call any intertwined knot or symbol a valknut.

Gjessen also notes in his article that the name valknute is found in old danish dictionaries. For example in C. Molbech’s 1833 Danish dictionary “Dansk ordbog” it states

Valknude , en . pl . r . En konstig knyttet Knude , som vanskelig kan løses og eftergiores

Valknot, An artifically tied knot, that is difficult to untie and undo

Note that an even earlier occurrence of the word comes form the 1807 Danish-English dictionary by Christian Friderich Bay, with the simple translation:

Valknude, a Waleknot

i.e. a nautical knot used as a stopper on a rope, often used in conjunction with the term “wall knot” today, which in many respects is similar to a Gordian knot. Note that occurrences of the term “wale knot” date back much earlier and can be found in for example Sir Henry Mainwaring’s book “The sea-man’s dictionary” from 1670.

The term “valknute” therefore has historically referred to a long list of somewhat related symbols. However, the word’s translation to “Waleknot” in Danish from 1807 seems to strongly suggest the etymological basis for the word is not from “valr” such as suggested by Gutorm Gjessen, but rather a “Scandification” of the otherwise well-known nautical term “wale knot” – referring to a nautical knot.

Contextual interpretation

Having extensively discussed the etymology behind the modern name for the symbol we should shift focus and actually look at the symbol itself, disregarding it’s epithet.

Context is essential in interpreting anything related to the vikings. Not only is much, if not all, symbolism and mythology to the vikings the result of broader influences from other civilizations. We cannot deny the similarity between for example old Norse deities and those of Greek or Roman mythology.

Very little of the viking’s world view evolved in a vacuum. There are probably many occurrences of the symbol known as “valknut” in contexts other than that of the Scandinavian vikings, where the symbol has other interpretations. The valknute has similarly been found on an extensive number of artifacts both within and outside Scandinavia. We will in this context only concern our self with the Scandinavian finds.

In Norway the symbol has been found on the bedpost form the Oseberg burial ship and on a bucket lid from the same burial. In Denmark it has been for example been found on coins from the Damhus hord. While Sweden has the largest amount of finds, where it is found on several picture stones. Let us briefly describe some of these finds.

From Sweden on the Tangelgårda Stone the valknut is found around the legs of a horse with a rider, most often interpreted as warriors entering Valhalla. The rest of the imagery on the stone is generally also believed to depict stories about the mythology surrounding Odin.

On Lillbjärs III (G268/GP 390) the symbol is again next to a rider and horse riding towards a figure holding a horn in what looks like a welcoming. Below the central scene is a ship. It is tempting to interpret this scene similarly to the scene described above of a warrior being welcomed into Valhalla, given their visual similarities. However suggestions have been made that the scene depicts Sigurd being welcomed by Brynhildr or the Saga of Hild. The same rider and symbol is also found on the stone Lillbjärs I (GP 388) from the same location. Both these stones are found in a well-known Migration-period burial site, and have possibly acted as headstones.

On Stora Hammars I, the valknut is seen next to a depiction usually interpreted as a human sacrifice (sometimes believed to be a “blood eagle”) and two birds. The rest of the stone also depicts a ship and also the image of a warrior about to be hung on a tree, among other scenes.

On the stone Hejnum Riddare we see a ship with a symbol placed near the aft. This symbol is valknut-like, but where the triangles have been pulled apart, hinging in the corner.

Regarding the coins from the Damhus treasure in Denmark, the conclusion reached by Claus Feveile is that the horse-like animal on the coin is a deer. Equally he notes that the reverse side of the coin contains a face which is similar to faces on other coins which are believed to be depictions of Odin (p. 55). Directly what the connection between a deer and Odin is is not clear, but the symbolism between the valknut and Odin seems to persist. Concurrently, the other style of coin has the same deer and a ship on the reverse side. It is not clear to us if there is a valknut on any of these coins, however we know from the Swedish above picture stones that the valknut has been depicted in relation to ships.

According to Gutorm Gjessen the valknut has also been carved into doorways and artifacts throughout the times, eventhough we have no clear evidence of this.

Interestingly, G. I. Schive makes the following interpretation in regards to the triquetra symbol viewed above which seems similar to the valknut found on the Hejnum Riddare picture stone:

Tre sammenlagte Skjolde, eller maaskee en ufuldkommen udfört tredobbel Slöife eller Valknude, der har den symbolske Betydning af Treeningheden.

Three joined shields, or maybe an incomplete bow or valknot, which symbolizes The Trinity.

This is actually a pretty interesting claim if correct. We know very confidently that a common theme during the Christianization of Scandinavia was to take the old symbols and customs and partially or completely change them into symbols of the new faith. Many churches were built on previously sacred places, and several Norwegian stave churches have runic inscriptions and carvings. For example Thor’s hammer was gradually replaced by the christian cross, as demonstrated by the crosses/hammers found both in Huse in Norway and on Iceland which both looks like a hammer and a cross. It would in this regard reasonable that the symbol associated with one of, if not the, principal deity of the pagan faith would be modified slightly and used to symbolize the new faith in order to merge the ideas between Odin and the Christian god. This could further strengthen the idea of the valknut as a symbol for Odin.

Based on this we feel it is reasonable to see the valknut in a Scandinavian Viking-era context as a symbol either of Odin or of death. The discussion of the connection between these two ideas is best left for another time. The most likely explanation nonetheless would be that it is a symbol of Odin directly. The symbol’s function as a invocation of Odin and equally perhaps a protective symbol or sigil would also help explain the carving of the symbol into everyday items such as the Oseberg bedpost or bucket lid.

This idea is the same as reflected by Gjessen from the quote above where the valknut and its related symbols, such as the triquetra and the St Johns’s Cross is believed to be protective symbols in Norwegian folk religion and superstition.

Having a symbol of Odin directly would also be likely in an old Norse context, who were known to use symbols to depict deities and ideas. To make a related example to more accurately relay this, we can look at Thor’s Hammer Mjölnir. On the Altuna Stone a human figure is depicted holding a hammer in one hand. Due to the inherent symbolism related to the hammer we know definitively that the figure on the stone is Thor. Had the figure not been holding a hammer there could have been questions raised about who the stone depicts, as it contains no text describing the scene. Concurrently people would extensively wear Thor’s hammer as an amulet or talisman, maybe the same way the valknut was carved into objects in the Oseberg find.

In the context of Scandinavian vikings, a common interpretations among researchers either way seems to be that the motif most commonly known as valknut is a symbol related to Odin and secondary ideas connected to him. Furthermore, on the basis of Gjessen’s ethnographic interpretation of the symbol in a Scandinavian-Viking context, seeing the symbol as representing Odin is not unreasonable, but it is obviously etymologically questionable.

Conclusion

The takeaway from this article is probably that there is no real conclusion, as we can never fully decipher the intentions of a people who did not thoroughly record their intentions for prosperity. Nor can we make any attestations to the universal interpretation of the symbol valknut.

Furthermore, we cannot definitely say that valknut, valknute or valknutr was the name for the symbol we have discussed. Nor can we say anything about whether the term valknutr was known to the vikings at all. However, all evidence indicate that the name is a purely modern invention, applied to a range of similarly knotted symbols. A likely explanation for Gutorm Gjessen using the word “valknute” to denote the symbol, can in large part be explained by his willingness to draw parallels between the word’s prefix and its association with Odin.

However, getting trapped in a debate about the etymological origins of the name of the symbol and thereby using this name as a way to dismiss its symbolic significance is possibly an even bigger crime.

There is overwhelming evidence that the Vikings in Scandinavia often would use the symbol in relation to depictions interpreted as being of Odin. Therefore many researchers seem to believe that in this context the symbol was associated with Odin. We have found no evidence which opposes this and therefore see the symbol as a likely invocation of the Norse god Odin.